An archived Nikkei article recently caught attention with a striking comparison:

average monthly wages in Tokyo are roughly half of those in New York.

At first glance, this gap seems to suggest a simple conclusion — Japanese companies must be less profitable.

In reality, the situation is far more complex.

The wage gap between Tokyo and New York is not primarily the result of weaker corporate profits, but of how profits and value are distributed.

Exchange Rates Matter More Than They Appear

The first factor to consider is currency.

Salaries in Tokyo are paid in yen, while salaries in New York are paid in US dollars.

When the yen depreciates, Tokyo wages look significantly lower when converted into dollars — even if real purchasing power has not changed as dramatically.

This means that headline comparisons such as “Tokyo wages are half of New York’s” can exaggerate the perceived gap.

Profit Levels Do Not Directly Translate Into Wages

A common assumption is that Japanese companies pay lower wages because they generate less profit.

However, this assumption does not hold up under closer examination.

Many Japanese firms are consistently profitable and financially stable.

Yet their wage levels remain lower than those of US firms, not because profits are absent, but because profits are allocated differently.

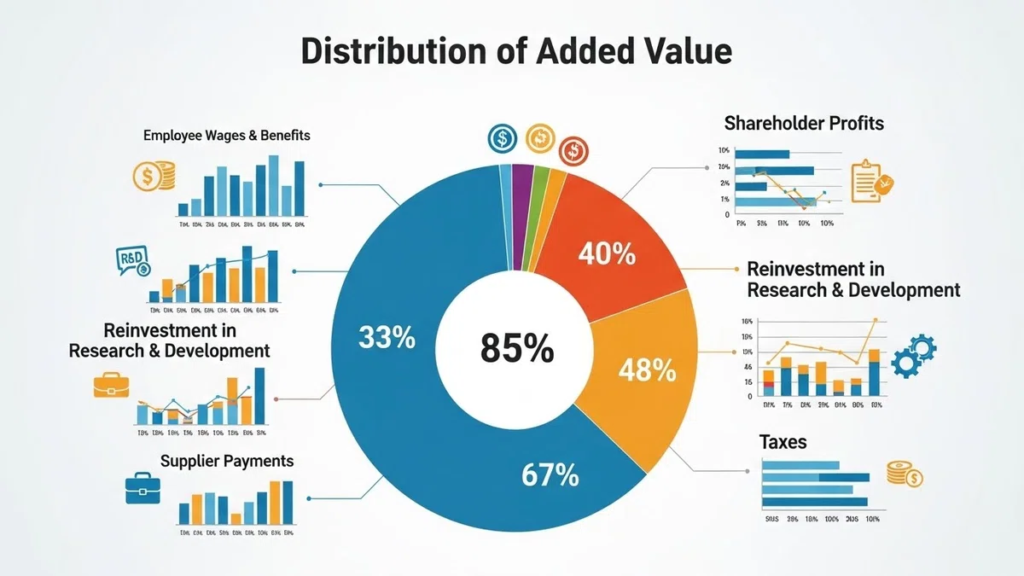

The Key Difference: Value-Added Distribution

To understand the wage gap, it is more useful to focus on value added, rather than headline profit figures.

Value added represents the wealth created internally by a company after subtracting external costs such as materials and outsourcing.

This value is typically distributed among:

- Employee compensation (wages and benefits)

- Shareholder returns (dividends and share buybacks)

- Internal reserves and capital investment

- Taxes and social security contributions

The primary difference between Tokyo and New York lies not in how much value is created, but in how that value is divided.

Bonuses and Total Compensation

Japanese companies often keep base salaries relatively low while paying significant semi-annual bonuses.

These bonuses are increasingly performance-linked and variable.

In contrast, US companies tend to offer higher base salaries, with bonuses that are less predictable and more individually performance-based.

When total compensation — including bonuses — is considered, the wage gap can appear smaller than monthly salary comparisons suggest.

Welfare, Risk, and Corporate Responsibility

Another structural difference lies in welfare and risk allocation.

In the US, healthcare, pensions, and retirement planning place a heavier burden on individuals.

Higher wages compensate for this risk.

In Japan, companies have historically absorbed a larger share of social security, retirement benefits, and employment stability.

This has suppressed cash wages but provided long-term security.

In other words, lower wages in Japan often reflected stability and protection embedded within employment, rather than weak profitability.

A Model Under Pressure

This traditional model is now changing.

Labor shortages, inflation, and shareholder pressure are pushing Japanese firms toward higher wages and stronger capital efficiency.

Early retirement programs and increased dividends and buybacks are signs of this transition.

As these pressures intensify, the structural wage gap between Tokyo and New York may gradually narrow — though not disappear entirely.

Conclusion

Tokyo’s lower wages are not a simple reflection of unprofitable companies.

They are the result of long-standing choices about how corporate value is distributed — between wages, stability, shareholder returns, and social security.

Understanding wage differences requires looking beyond headline numbers and examining the entire compensation and value-allocation structure.

Thanks for always supporting me! If you like my content, a cup of coffee’s worth of support would mean a lot.

コメント